Introduction

In the past, by which I mean as far back as you want to go, but particularly the 1920s, 1930s etc, the primary method of opposing a political movement or tendency was to do so directly. Political battles on the streets, electoral contests involving propaganda and shows of strength etc; books might be written, too. One thinks perhaps of Trotsky’s book Terrorism and Communism, largely a polemic against the social-democrat Karl Kautsky. That was then. Today, while elements of the former methods still exist, new ones have come to the fore. One of these, applied particularly to (deployed against) the nationalist wing of politics, is the fake party, fake movement, fake tendency (call it what you will).

Fake Movements: example

It may be that the modern “fake movement” tactic had its genesis in the repressions of the Russian Empire in the period before the First World War. The Tsarist secret police, the Okhrana, established agents as “dissident” voices, attracting to those agents genuine dissidents. Thus society had “safety valves” and could blow off steam safely, with no danger of serious damage to the overall society or the government’s hold on the people.

There were many examples. The famous Father Gapon became one such, though it seems that, like his even more famous predecessor, Judas Iscariot, he started off as an “honest dissident” or believer in social justice. Likewise, the assassin of Stolypin was another “double agent” or double player, being both a revolutionary and an agent of the Okhrana.

Fake Movements Today: UKIP and how it was used to beat down the BNP; the Alt-Right fakery now joins with UKIP to prevent the rise of any new and real social-national party…

It is of the essence of a “fake” movement that it starts off or seems to start off as a genuine manifestation of socio-political frustration. UKIP was like that. It started life as the Anti-Federalist League, the brainchild of a lecturer at the London School of Economics, Alan Sked, whose first attempt at electioneering led to a 0.2% vote (117 votes) at Bath in 1992. UKIP itself was created in 1993. At that stage, UKIP’s membership could be fitted into one or two taxis.

By 1997, UKIP was able to field 194 candidates, yet still only achieved 0.3% of the national vote, perhaps equivalent to 1% in each seat actually contested, the same result as had been achieved in the 1994 European elections. In those 1997 contests, the Referendum Party funded by Franco-Jewish financier James Goldsmith was its main rival (beating UKIP in 163 out of 165 seats). The BNP was another rival, on the more radical, social-national side. However, the votes of all three combined would have amounted to only a few percent in any given seat.

It is at this point that an early joiner, Nigel Farage, emerges as leader. Alan Sked left UKIP, fulminating about “racism” and Farage’s meetings with BNP members etc. Farage had been the only UKIP candidate to have saved his deposit in 1997 (getting 5% at Bath, Sked’s old test-bed). Goldsmith died; most of the Referendum Party joined UKIP. “Major donors” emerged too.

In the 1999 European elections, UKIP received 6.5% of the vote; not very impressive, but enough (under the proportional voting system in use) to win 3 seats in the EU Parliament. From that time on, UKIP slowly gathered strength. In the 2001 general election, it still only had 1.5% of the national vote, but 6 of its candidates retained their deposits.

On a personal note, I missed much of UKIP’s rise. I was living out of the UK for much of 1990-1993 (mostly in the USA), again in 1996-97 (in Kazakhstan) and after I left Kazakhstan again spent much time overseas (many places, from North Cyprus to the Caribbean, the USA, the Med, the Canaries and Egypt, among others). In any case, I was not much interested in UK politics at the time. I had lunch with a girl in a pub at Romsey in Hampshire in the Spring of 2000. She told me that most of her time was spent “working on behalf of something called UKIP. Have you heard of it?” Answer no. When it was explained to me, I have to admit that I thought, secretly, that something like that had no chance. I suppose that I was both right and wrong at once.

Now, at the time when UKIP was gaining strength, after 1999, the BNP under its new leader, Nick Griffin, was also gaining strength and –in Westminster elections– doing better overall than UKIP at first. In 2001, it got over 10% of the vote in 3 constituencies (16% in one). It is important to note here that the BNP was a genuine party, proven as such by the hatred it engendered in the “enemy” camp(s): Jewish Zionists, “antifascists” (many of whom are also Jews, though some are naive non-Jews), and the System (a wide term but certainly including existing MPs, the BBC, the journalistic swamp etc).

The anti-BNP forces were trying constantly to repeat their success in destroying the National Front in the 1970s. It lived on after the 70s, but as a shell. Internal factionalism was aided and abetted by skilled enemies. Akin to cracking marble in Carrara.

Whatever may be said of Nick Griffin (and I am neutral on the subject, though certainly more sympathetic than hostile), it cannot be denied that he gave the BNP its only chance of becoming a semi-mainstream party in the manner of the Front National in France. A strategic thinker, he managed to bring the BNP to the brink of success by 2009.

Within UKIP itself, there were social-national elements as well as what I would call conservative nationalists and others who were really Conservative Party types who, being anti-mass immigration, anti-EU etc, had defected. Two of the last sort later became UKIP’s 2 MPs, both initially elected as Conservatives: Mark Reckless, Douglas Carswell. Their kind of pseudo-“libertarian” “Conservatism” was exactly the wrong position for UKIP to take and positioned UKIP somewhere near but beyond the Conservative Party, when, to really break through, it needed to go social-national.

When the BNP imploded after the disastrous post-Question Time 2010 General Election, UKIP was able to get the votes of most of those who had previously voted BNP, if only fuelled by frustration or desperation, or “better half a loaf than none”.

UKIP beat all other UK parties at the 2014 European elections, getting 27 MEPs. OFCOM then awarded UKIP “major party” status, enabling it to get huge amounts of airtime (and people still talk about Britain’s “free” mainstream media…).

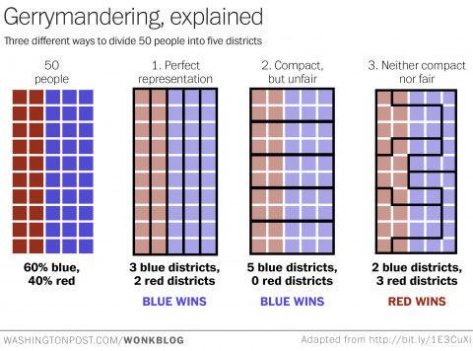

UKIP however, was unable to beat its way through the British fair-seeming (but in fact as good as rigged) “First Past the Post” electoral system at the General Election of 2015. 12.6% of national vote (nearly 4 million votes), but only 1 seat (Carswell’s, at Clacton, Essex). Meanwhile, the BNP vote had collapsed even from its 2010 level (1.9%, 563,743 votes) to effectively zero (1,667 votes).

I myself had already tweeted and blogged from 2014 that UKIP had peaked. I paid virtually no attention to the BNP, which by that time was already yesterday’s news. The 2017 election brought UKIP 1.9%, whereas the BNP bumped along with statistical zero (despite having tripled its individual votes to 4,642).

Douglas Carswell, the “libertarian” Conservative faux-nationalist resigned before UKIP’s 2017 failure to take up lucrative “work” in the City of London. His work with UKIP was done, let us put it that way. As for Farage, he reinvented himself as a touring talking head, while keeping his hand in as a “nationalist” by referring to his concerns about the “US Jewish lobby” (strangely, he failed to mention the Jew lobby in the UK or France…).

Today, in 2018, with neither main System party commanding firm support, we see the System, the Zionists in particular, “concerned” about the “resurgence” of the “far right” (i.e. worried that the British people might awaken and turn to a real alternative).

So what happens? The System “operation” revs up a little: the “Alt-Right” talking heads –who rarely if ever criticize the Jewish Zionist lobby– are now flocking to join UKIP! Milo Yan-whatever-he-is-opolous, “Prison Planet” Watson, “Sargon of Akkad”, “Count Dankula” etc…all the faux-“nationalist” fakes and fuckups are going to UKIP, have in fact gone to UKIP, have all suddenly joined as members of UKIP.

Conclusion

Naturally, all this could be co-incidence, but it is very odd that the events that I have chronicled seem to have happened at just the “right” time:

- UKIP rising at the same time as the BNP which was, at that time, a rapidly-growing potential threat to the System;

- Nick Griffin ambushed on BBC TV Question Time;

- BNP marginalized in msm while UKIP was promoted as a “threat” to LibLabCon;

- UKIP given endless msm airtime so long as it was “non-racist” (it now has quite a few non-whites as prominent members and is pro-Israel etc…);

- Conservative Party MPs defecting to UKIP and so (in the absence of any elected UKIP MPs) bound to take leading roles in UKIP and steer it into capitalist, “libertarian” backwaters;

- as the people look ready to follow any new credible social-national party (were one to emerge a little further down the line), suddenly dead-and-nailed-to-its-perch UKIP gets a boost from those fake “Alt-Right” figures…;

- Former msm “radical” talking heads such as Paul Mason turn up shouting about the UKIP/Alt-Right convergence as if the SA were marching down Whitehall.

It is just all too convenient.

Still, God moves in mysterious ways. Maybe the System, in its cleverness, will score an “own goal”. After all, that’s what the Okhrana did in pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg…

Notes

https://archive.org/details/storymylifebyfa00gapogoog

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UK_Independence_Party